How do the feasts that God commanded Israel to observe relate to me today? Well, the most prominent way has to do with the timeless truths and principles that each feast reveal concerning the nature of our Heavenly Father, and what He cares about. The study available for use is all about how to apply these feasts in principles of life.

The Principle Approach: “The Feasts of the Lord” What the Feasts of Israel Teach Each Generation About Walking with God (Leviticus 23)

Nearly everyone enjoys the holiday season. It seems that we are creatures geared to occasional breaks from our labor and always look forward to holiday festivities. We make holidays of our own birthday, and of the birthdays of other “famous” men. We even make those birthdays fit into Mondays to have the long holiday weekend accepting no sacredness of accuracy. We make a holiday of the passing of each year into the next, in a calendar system of our own creation. It seems we can always find a reason to cease our labor, and party! Holidays not only give us a chance to have fun, they also express something unique about who we are, about what we treasure. Take for example the Independence Day celebrations of each nation. Depending on which you celebrate, you align yourself uniquely with the history of that country. In addition, there are the “religious” holidays that may express something about your theological affiliation.

The Hebrew Scriptures specifically instruct the observance of seven holidays and one special weekly observance called the Sabbath. These eight special observances, unlike other holidays, are directly mandated by God. They are, in fact, a part of God’s law, or Torah for observance by Israel. In order to really understand why God instructed that each special observance be held, we must understand the reason God gave the Torah to the children of Israel . The ancient Israelites had lost much of their spiritual heritage in bondage, and this would be restored in the Sinai wilderness. Hot off the desert sands from their trek out of Egypt, the ancient Hebrews had seen God move miraculously and decisively to set them free from their bondage. They had seen God defeat their foe. They watched in wonder as the mighty arm of the Lord worked in power through their once exiled shepherd prince. Moses, now late in years and yet mighty in faith, had begun a vital and thriving relationship with the God of his fathers some years before, after a “burning bush encounter” in the Midianite desert. Now Moses had thousands of refugee Israelites following him and trusting that his relationship with the God of Abraham would yield their freedom and safety.

To Sinai they went, this rabble of ex-slaves following their shepherd prince. They arrived three months into their rugged journey (Ex. 19:1), to pitch their tent beneath the shadow of the mountain that would change their future forever. They arrived uncertain of their fortune, uncertain of their God’s purpose. Only a handful had any real understanding of the God of Abraham. Even their leader had to ask the name of the God of Abraham on his previous encounter at the burning bush. Much spiritual heritage had been lost in their prolonged bondage. At Sinai they heard the voice of their God. He made clear the standards, values and ethics of this unique nation. He revealed His unique relationship with them. He would share his loving heart and righteous Spirit. The festivals outline the key life principles each person would need to understand to walk in a pleasing way with the God of Abraham. Within this law, the God of the Hebrews gave careful instruction for the children of Israel to observe eight specific holidays. They were not intended to merely be a break from labor, they were to reveal something special and important about the God who gave them. They demonstrated God’s desire for His people. They outlined key life principles that paved the way for all the necessary lessons in living in obedience to Him. When we carefully examine the festivals and observances in Levitical law (Lev. 23), we find that God has outlined the key principles that reveal his plan for His people. This plan includes a relationship with the children of Israel, and a plan for their spiritual redemption. God’s instructions in the Torah were not given to take fulfillment and satisfaction from man. On the contrary, God instructs that each observance be carefully passed from generation to generation (Dt. 6:1-25). In every mundane and ordinary moment of life children were to be exposed to the Words of their God in order that His people may receive the best in life (Dt. 6:24) and live the most rewarding of lives!

Exposing the Principle In The Sabbath

Before introducing the observance of any of the annual cycle of feasts, God revealed once again that His call for the weekly Sabbath is as important as the other “holy days” of the calendar. God had specifically marked one day in seven for man to stop his work, and spend that day in a unique “rest celebration” of his Creator. God was not short on His instruction for the Sabbath (which means rest). Instructions can be found in Exodus 35, Lev. 25, Num. 15 and Dt. 15:32-35. God outlined that both man and work animals would rest from their labor, and that this observance would be a memorial (Hebrew: Zakar, see Exodus 20:8) that would be kept distinct or “holy” from other days. A ten year old boy went into his rabbi one day and asked the question, “Rabbi, if God got tired after all His creation work, why did He make a holy day to celebrate it?” It was not an easy question, but the Hebrew Scriptures are clear about the answer. In short, God did not reveal the Sabbath to celebrate His rest, but to teach us something important about our needs! The Sabbath is specified to be three things: a time of rest from labor (Gen. 2:2,3; Ex. 16:23); a time of obedience (Ex. 20:8-11); and a time of identification (Ex. 31:12-17).

1. A time of rest: God taught His people the need to complete a cycle, to take “time out”. He provided in this time not only a cessation of work, but also a special time to meet with Him, to learn of Him and develop a heart to follow Him (Num. 28:9-10; Ps. 92; Isa. 1:13-15). It was a time to deal with sin, start fresh in the walk of obedience to God, to rethink the way things were done in the preceding week.

2. A time of obedience: God did not simply want compliance to a list of rules. He has always desired a personal relationship with men. The commandments (Ex. 20) were given that men might have a way of expressing their personal faith in fruits of life. They were expressions of behavior, rather than just hollow words of belief.

3. A time of identification: The Sabbath was to signify the covenant God had made with the children of Israel (Ex. 31:12-17). The weekly celebration was to be a memory device so that the children of Israel would not forget the God of their fathers as they had in the bondage of Egypt. God was concerned that the success of the Israelites would take a more significant toll on their memory than slavery had before (Dt. 6). The Sabbath showed obedience, covenant relationship and the need for completing cycles in life. The Sabbatical principle was further underscored by the overall cycle of “sevens” God built within the calendar of the people. Not only was one day in seven dedicated to worship and rest, the seventh month was dedicated to the highest holy days of the year. The seventh year was to be a sabbatical year for the land (Lev. 25:2-7). And the seventh sabbatical year (every 49 years) was to be concluded with a “Year of Jubilee” (Lev. 25:8-25). God made his point clear: time apart from work was necessary. Time to learn and worship was essential. A time of reflection and anticipation was healthy. The Sabbath was truly made for the man! The need for rest precedes the instructions for all of the other holy festivals of Leviticus. Is it significant that this is the weekly observance in which the greatest time will be invested by those who observe it. The order of its appearance on this list significant. The principles of the Sabbath set the tone for the seven annual festival observances. The real message of the Sabbath is that we can rest in the Word of God, and His Word can absolutely be trusted! All of the principles found in the feasts will rest on one important premise: You can trust the Word of the God of Abraham, and can rest in His holy revelation of Himself given in the Torah. That is the lesson of the Sabbath. It is expressed by the ancient Psalmist: “The Law (Torah) of the LORD is perfect, restoring the soul: the repeated warnings (Eduth) of the LORD are sure, making wise the simple.” (Ps. 19:7) The Sabbath is listed first and foremost, that the children of Israel might clearly know that the God of Abraham can be believed and held accountable to His holy Word. Without this principle, no other principle will hold together.

Principles from the Cycle of Annual Feasts

The seven feasts are each given specific reference in Leviticus 23, and are listed in the order they will be celebrated in the calendar year. The spring festivals will include the first four mentioned, the last three are autumn festivals:

1. Passover (or Pesach, the first day of Unleavened Bread) Lev. 23: 4,5.

2. Unleavened Bread (the week of) 23:6-8.

3. First Fruits (the second day of unleavened bread) 23:9-14.

4. Weeks (also called Shavuot or Pentecost) 23:15-22.

5. Trumpets (also called Yom T’ruach or Rosh Hashanah) 23:23-35.

6. Day of Atonement (or Yom Kippor) 23:26-32.

7. Tabernacles (or Sukkot) 23:34-44.

The Principle from Passover

It was God’s instruction that the first holy festival be an observance that would clearly mark a believer from the unbelieving world in which he lives. The story behind the passover is familiar to even the most casual Bible reader. It is a story of the great work of God setting the children of Israel free from bondage in Egypt. After generations of serving Egyptian Pharaohs, the cries of the children of Israel went up before the Lord God, and He sent a deliverer to release his captive children. After a series of plagues designed to change the mind of the fickle Pharaoh, God finally pronounced that He would send a plague that would be forever remembered. Exodus 12 records that the power of God would strike down the firstborn of every home in Egypt not protected by the mark of lamb’s blood on the door or tent post. The great story of redemption unfolded as Pharaoh freed the children of Israel amidst the wailing of Egyptian mothers who had lost their firstborn. The God of Abraham proved too powerful for the mighty Pharaoh of Egypt. The purchasing of the freedom of God’s people was forever to be symbolized by the Passover feast. The instruction given by God to Moses was to be continually observed. A close look at God’s instruction yields the clear principle He wanted each generation to understand. God wanted each generation of Israelites to understand that individual belief, and individual use of the blood would be necessary to be saved. Exodus 12:3-5 gave careful instruction about the preparation of the home before the Lord executed judgment on the Egyptian firstborn. Each man was instructed to take “A LAMB” (12:3) for his house. If “THE LAMB” (12:4) was too much for the small household, the man was to share with his neighbor and not waste. The lamb was to be spotless, sacrificed that its blood may be used as a marker. It was to be killed and personally applied as “YOUR LAMB” (12:5). Individuals would have to use the blood. Individuals would then have to wait and trust that God would keep His word. They would have to silently wait and trust that the blood was enough to protect them from the judgment of God. The message for the children of Israel was compelling: they needed to personally believe the message of God, and follow the direction of God to be saved from calamity and set free from bondage.

The Principle from the Feast of Unleavened Bread

The day after the Passover sacrifice and meal, a week long festival ensues (Lev. 23:6). The focus of this feast was the eating of “unraised” or unleavened bread, and later with the total cleaning out of the tent or home. Instruction on the festival is given in Exodus 12:15-20 (cp. Lev. 2:11 for leaven). Between two Sabbath rests, this week long observance was intended to remind them that “the Lord brought the children of Israel out of Egypt” (Ex. 12:17). Leaven was specifically mentioned by God in connection with offerings and sacrifices. Lev. 2:11 excluded its use in most of the sacrifices because it was a fermenting influence and corruption of the sacrifice. God held a special regard for materials used in sacrifices to honor Him. Leaven was corrupt and unusable in this context. It is from this we can extract the life principle God taught His people: It was not enough for them to come out of Egypt. Egypt, and its corrupting influence needed to come out of the people. The principle behind the cleaning out of the leaven was well illustrated by the teaching of an old fisherman. The fisherman took his small boat out to sea early each morning to catch the fish for the market. He moved along the surface of the water with great ease, for the boat was well designed for fishing. On one occasion, the old fisherman took his son with him to the sea. His son was unaccustomed to the boat and began to tip the small craft as he walked around inside it. The older fisherman raised his voice and exclaimed, “Sit down! The boat is fine in the sea, but we don’t want the sea inside the boat!” The principle of cleansing the house from leaven (chametz cleansing) was an illustration of the need to live a life of separation from corruption and sin. That same “keep the sea out of the boat” principle is the message of the feast of Unleavened Bread, a message of a clean walk. Theologians use the term sanctification, which means “set apart for a specific use, often a holy use.” The usable vessel must be free of leaven. It must be clean. The God of Abraham desired to use men to accomplish His work. These people, however, had to be periodically cleansed and renewed. The children of Israel were taught to walk with a view toward holiness, a view toward separation from sin.

The Principle in the Feast of First Fruits

The Sabbath had given the children of Israel the necessary understanding that a close of cycle and rest was necessary. What the Sabbath did for the end of one’s work, the feast of First Fruits outlined for the beginnings of life. The beginning of the harvest was the setting for this important lesson. The instruction concerning this festival (Lev. 23:9-14) specifies the amount of sacrifice to be offered to the Lord at the coming of the first harvest (normally the barley harvest). The timing of the observance was normally the second day of the unleavened bread observance week. The message of the feast of first fruits was that God is above all, the Sustainer and Owner of all. His people are to be stewards of His property. God wanted the children of Israel to understand what He had provided for them, and how they were to respond to His gracious giving. All they possessed was undeserved blessing (Dt. 6), and all they had belonged to God (even their children, see Ex. 13:2). God’s clear instruction was to take of the first of the harvest and give an offering back to Him. The offering served several functions:

1. IT WAS AN OFFERING OF THANKSGIVING. The unmixed and unsettled wine from the new harvest at the end of the previous summer was poured out on the small offering of grain, as instructed in Exodus 29:40,41. With the pouring out of the wine was a joyful offering of praise, thanking God for providing anew for His people. God’s provision would allow Israel to remain strong and stable for another year. The planting and work had been blessed by God as He brought forth “bread from the earth”.

2. IT WAS AN OFFERING OF ANTICIPATION. Because the offering was the “first fruit” of what was to be gleaned from the barley harvest, much of the field had not yet been readied for harvest. The offering pressed a reminder to all the people that the harvest allowed them to steward what God was giving. He was the owner of the harvest. He was the secret to their success. They could anticipate more harvest, because the God of Abraham is a good God, desiring to bless His people.

3. IT WAS AN OFFERING OF ACKNOWLEDGMENT. By offering of the harvest before the rest of the harvest was brought in, God impacted on the people the lesson of acknowledging their need of Him. Even after the crops had grown, much harm could come to them. Infestation or fire could wipe away all the yield for the year. The people needed a reminder that God was not an “extra” in their lives, He was the sustainer of Israel. His offering came first, because He had preeminence over all in Israel!

The Principle in the Feast of Weeks

In Israel, the summer months are long, hot and dry for most of the land. The spring grass is withered and brown. The flowers that dotted the Galilee landscape give way to the dark rocks and dry weeds that cover every uncultivated field. The time of the long awaited first rains of Autumn usually produce celebration, as children go outside in the rain and dance for joy (even some of us as adults join them)! The rains awaken the land to new life, and the promise of another harvest! The harvest is the life blood of any agricultural people, and the children of Israel awaited the harvest with great anticipation. The principle of Shavuot was that God’s plan and program included another demonstration of undeserved love… in spite of any corruption of the people. Fifty days after the festival of first fruits, the major part of the harvest was completed. The festival of Shavuot or “weeks” began. The Greek word for “fifty days” is Pentecost, and the festival receives this name in ancient Jewish sources from the Second Temple Period. Regardless of which name was used, the timing of the feast, and the peculiar instructions for the observance of the feast give the clearest indications of the meaning and purpose of this holy festival. This feast was truly a celebration of the harvest (it is called the “harvest feast”, see Ex. 23:16). It expressed the grace of God to His people in yet another year of meeting the needs of the people. It was another expression of God’s desire that the children of Israel be preserved and sustained. The people, undeserving of God’s mercy and grace, would receive from the mighty hand of the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The celebration illustrates the undeserving people that God was blessing. In contrast to the feast of “unleavened bread” where all leaven was to be purged from the sacrifice and it was to be clean of fermenting corruption, the feast of weeks includes two loaves of meal baked with leaven (Lev. 23:17). The leaven was prescribed as part of the ceremony, and obedient faithful could do nothing less than obey. Why include the leaven in the loaves? What was God’s intention in this shadowy symbol? Why allow a corrupting influence in His holy worship? The symbol helps to illustrate yet another facet of the character of the Lord God. The leaven in the loaves at Shavuot aren’t the only corruption that was found in the festival, there were people there. By nature, the children of Israel were constantly unclean, constantly influenced by the world outside. They were not pure. They had the corrupting influences of leaven always present with them, yet God had mercy on them. God’s lovingkindness (hesed) was undeserved, yet liberally dispensed. Shavuot allowed the people to remember that God’s program and plan included grace, year after year!

The Principle of the Feast of Trumpets

The Jewish cycle of the year includes the combination of an ancient harvest calendar, and the annual cycle of the religious festivals that God prescribed. It is because of the combination of calendars that there are literally several “New Year’s Days” in the calendar. In rabbinic tradition, there is even a new year beginning for trees. The tradition shows great respect for the Creator, and for His handiwork. The “Day of Trumpet Blowing” (Yom T’ruach) was prescribed by God as the beginning of the civil year, or “secular” year. It was prescribed as the beginning date for financial transactions, for market purposes, and for military services. It also introduced the highest holy days of the month Tishri, the sacred seventh month (by religious calendar reckoning) that contained the highest holy days. Of all festivals, the Feast of Trumpets could appear to be the least important. It was simply the ringing in of a new civil calendar year. Why would God include this in His list of sacred observances (Lev. 23:23-25)? What significant life principle did the Lord God desire that the children of Israel understand? Certainly part of the purpose of this holy assembly was to again symbolize that the nation of Israel was a part of the special program of God (Ezek. 37:3). In addition to this symbol, a careful examination of the specific observances during this sabbatical rest showed it was even more significant as a teaching device (cp. Num. 29:1-6). Extensive offerings were prescribed, demonstrating that God’s purpose was to emphasize a spiritual message amidst an otherwise secular event. In this God signaled the real message of this observance. To separate the “sacred” from the “secular” violated the very spirit of the Torah. God showed that the two were to be one in the Feast of Trumpets. God knew that it would forever be a temptation to the children of Israel to compartmentalize their faith into only one part of their lives. To segment between the “sacred” and the “secular” parts of their lives. The teaching of the law was to avoid this practice. God was to be Lord of all parts of the lives of the people under the covenant. He wanted every aspect of their lives to demonstrate that they were a nation with a royal and priestly heritage. Even the wearing of the royal blue ribbon in the prayer shawl (tallith) and tassels (tsit-tsiot) was to help remind them of the special relationship (Num. 15:38ff). If the God of Abraham was to have a people that would walk in relationship to Him out from the Sinai desert, they needed to understand His heart’s desire. He did not simply ask for some small religious segment of their life. Their faith should not be separate from the functions of life. Their faith was to be demonstrated in particular obedience to Divine direction. Sacred and secular were to be one, all under the leadership of the Lord God!

The Principle of the Day of Atonement

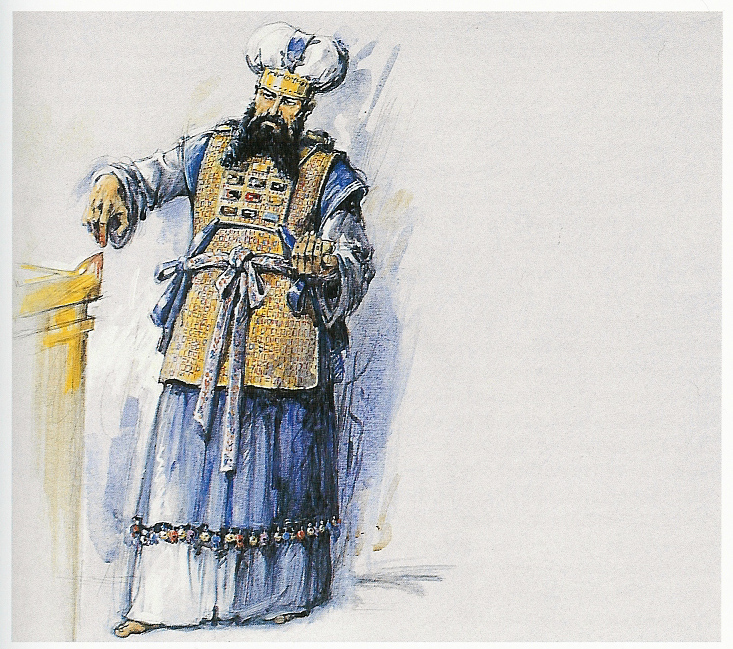

Ten days into the month of Tishri, God commanded the Day of Atonement to be observed by the children of Israel (Lev. 23:26-32). The feast was given as the most solemn of all the occasions of the sacred calendar, for the high price of sin was commemorated in the sacrifice. The command was given with serious tone, that each of the children of Israel would be impressed the seriousness of the day (Lev. 23:29) or they would be cut off from the house of Israel. Shepherds from all throughout the land of Israel understood the significance of the sacrifice to Israel. For months, they cared for and cautiously groomed the livestock that would be used for atonement sacrifices. The price of sin was paid by the animal suited for sacrifice. The solemn Sabbath was observed by the High Priest of the nation, as he adorned the priestly garb and made a sin sacrifice at the Temple (Lev. 16:29-34ff). The sin offerings were prescribed to include a sacrifice for the sin of his family, then an offering for the cleansing of the sanctuary, and finally an offering for the sin of the people of Israel. The sin was to be atoned by the sprinkling of the blood of the spotless sacrifice on the Mercy Seat of the Holy of Holies. The high price of sin, and the requirement of blood sacrifice to restore the relationship of God to His people was the message of Yom Kippor. The price of sin had to be paid in the atoning sacrifice that included blood. God gave the altar as a place of mercy to the children of Israel (Lev. 17:11). The blood that paid for sin was shed at the Temple, as the people of God observed the graphic display of the price of their sin. This memorial was designed to impress on each one who observed, that sin has an incredible price. The separation of the God of Abraham from his people could only be restored in the sacrificial system. Sin broke the sweetness of that special relationship – sacrifice of blood alone could restore it.

The Principle of the Feast of Tabernacles

The feast of Booths, Tabernacles or Sukkot reminded the children of Israel of God’s great work of salvation from the bondage of the Egyptian Pharaohs. The children of Israel were commanded to live in huts (Lev. 23:42) or booths during the week of the festival (see also Neh. 8:14-18), to remind them of the travel through the wilderness. Sacrifices during this time were prescribed to include 189 animals (Num. 29:12-38), and the week was full of reminders of the faithfulness of God in the wilderness journey (Lev. 23:43). The faithfulness of God was taught to each generation of Israel as they sat in their booths, recalling the wilderness journey. The time of Sukkot in Israel was originally the “end of harvest” feast (cp. Ex. 23:17), also called the “ingathering”. The autumn harvest was now nearly completed. After the long and hot summer months in Judea, God had again shown His faithfulness to Israel in bringing in the “miracle crop” of grapes. The olives and grain harvests now all stored, the celebration of God’s faithfulness to the children of Israel completed the calendar of sacred observances. God had shown Himself merciful and faithful to the children of Israel in the desert wilderness. The dividing of the Sea, the manna of the wilderness, the cloud of guidance, and the pillar of fire were all images to be recalled to each new generation of Israelite children from within the sukkah, that they might remember and understand their Father in Heaven. At the end of the journey was their promised home, a land that was theirs by Divine covenant. God had freed the people, lead them, and finally gave them cities “that they did not build” with “wells they did not dig” (Dt.6). Israel was never to forget. Israel was to always teach their generations that the God of Abraham keeps His covenants. He is faithful to bring His people home.

The Principles That Reveal The Character of the God of Israel

God wanted the children of Israel to know more of Him than rules, laws, and Divine standards. The Torah was so much more. It was the expression of God’s heart. It was the expression of Who He is. It was the “spiritual training camp manual” for the wilderness journey. It was the guidebook for the ancient Kingdom of Israel. It was the outline of the key life principles that God desired His people to understand.

GOD’S WORD IS TO BE TRUSTED: God wanted the children of Israel to understand that His character was trustworthy, His Word ever true. He established for them a Sabbath, that they might celebrate a completion of weekly labor, and learn His Word.

INDIVIDUAL BELIEF IS NECESSARY TO BE SAVED FROM JUDGMENT: God gave a Passover feast to remind each generation that sin required the individual belief and appropriation of a sacrifice for payment. Blood must be shed for each individual to be saved.

HIS PEOPLE MUST SEEK A “CLEAN WALK”: God instituted the Feast of Unleavened Bread that his people might understand that holiness in the walk of life was to be actively sought, and lived.

GOD WANTS FIRST PLACE: God showed the people that He was to be preeminent in their lives, and that all that they possessed came from His hand of blessing in the Feast of the First Fruits.

GOD OFFERS GRACE: God showed His marvelous grace and loving acceptance of imperfect men in the leavened loaves of the Feast of Weeks.

GOD IS GOD OF ALL PARTS OF OUR LIVES: In the Feast of Trumpets, God showed His desire that men not “compartmentalize” their faith, but live out their belief in every aspect of their lives.

SIN HAS A HIGH PRICE: At the highest holy day of Yom Kippor, the children of Israel saw the horror of sin paid for in the life blood of the sacrificial animals. The blood of the sacrifice was the only way to atone for sin.

GOD IS FAITHFUL: As the Feast of Sukkoth observance taught of the faithfulness of God in the wilderness, so were His people to ever remember that He gave them a home. He keeps His word.

This video helps set the priesthood of the Tabernacle and the really strange sounding “Millu’im Offering” into principles for our walk with God:

This video helps set the priesthood of the Tabernacle and the really strange sounding “Millu’im Offering” into principles for our walk with God: