A student and former participant in one of the cruise programs we offer studying “The Life and Journeys of St. Paul” requested some of the materials that we hand out, so I am offering them in document files. I normally post in pdfs, but I am away with my laptop and don’t have the pdf maker program with me.

The file is a rather complete description of the Book of Acts and how it fits into the New Testament writings, with a summary of each chapters comments like “Cliff’s Notes on Acts”. If you want to use it, feel free as the material copyrights are owned by me.

Understanding the Book of Acts

The Story of Messianic Beginnings

The Book of Acts in the “New Testament” Collection

The term “New Testament” refers to a collection of twenty-seven first century writings that became the foundation of the faith and practice of Christianity. The collection was written primarily in the Greek language, the common language of the Roman world of that day. It contains four distinct types of literature: A biographical series on Jesus of Nazareth called the “Gospels;” a historical narrative of the progress of the early Messianic Jews and their later Gentile converts; personal letters called “Epistles;” and apocalyptic literature.

The four Gospels are named after their understood authors: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. They chronicle selective accounts of the life and work of Jesus of Nazareth in first century Judea, Samaria and Galilee. The historical narrative of the early movement of the followers of Jesus the Messiah (called “Messianics” in Hebrew or “Christians” after “Christos” – the Greek translation of the Hebrew term “Messiah”) is called the Book the Acts. Following the narrative are twenty-one letters of several early movement leaders, named either by the writer they are attributed to or by the city or person of their destination. The collection closes with one apocalyptic work (a prophetic literary form like Daniel of the Hebrew Bible).

The name “New Testament” was taken from the words of Jesus recorded in the Gospel According to Luke (cp. Luke 22:20). The term “testament” means a covenant or an agreement between God and man. In the case of the “new” covenant, the implication was that recent events had initiated a remarkable change in the relationship between God and man. The New Testament’s theme, therefore, is that a new provision had been made in the series of agreements (covenants) that God had made for His relationship with men, the terms of which are announced in these writings.

The collected writings of the New Testament span a remarkable variety of accounts, places, cultural settings and characters. As indicated, the record begins with the four accounts of the life and work of Jesus of Nazareth – a religious Jew of the early first century. The narrative traces His lineage, His birth in Bethlehem, His early life and childhood in the Galilee, His baptism in the Jordan River and His public ministry throughout Judea, Samaria, Perea and the Galilee. Jesus never wrote a book, and none of the account is from His hand. The accounts of His life and teaching were authored by several early followers (called “disciples”) of Jesus as well as some who never met Jesus personally (i.e. Luke the Physician). The four books act as early pamphlets to share the heart of the work and message of Jesus. The climax of each account is the cruel execution of Jesus by Roman crucifixion, and the victorious narrative of His Resurrection from the dead.

The disciples of Jesus took His teaching and the story of His Resurrection to many parts of the Roman world. They called on people to believe that Jesus was not only the long awaited Messiah promised to the Jewish people in the Hebrew Bible, but also the very Son of God that came in human form for all mankind (cp. Acts 17:32; Philippians 2). They spread a message referred to as the “good news” or literally “gospel” (Gr. euangellion). The core of this message was that God was singular in essence but multiple in personality. Jesus was God’s Son that came in the human flesh to the earth to fulfill a mission of bringing man into a relationship with the God of Abraham. The redemption price of mankind was the blood of Jesus, sacrificed like a lamb at Passover for the sins of men. They taught that God had accepted the death of Jesus as a sacrifice “once for all” (Heb. 10:11-14) and that all men, regardless of their race or background could be fully accepted by God if they trust the work of Jesus as the basis of their redemption. As emissaries of this message, they became known as “Apostles” (Gr. apostello, “one sent”).

The fifth book of the New Testament collection (called “The Acts of the Apostles”, or “Book of Acts”) is in part a travel diary of the pioneers of the gospel, and part an explanation of the issues and problems of the early communities of faith. These communities were called churches or congregations. The major theme of the book is an explanation of how the promised Messiah to the Jews became a part of the lives of many who were born Gentile. As non-Jews, they did not appear to be included in the promise of the Messiah, and most had never considered their need to be brought into a relationship with the God of the Hebrews.

The Author – Luke the Physician

Early church fathers of the first several centuries gave extensive witness that the third gospel was written by the “beloved physician” Luke (cp. Col. 4:14), the companion of Saul of Tarsus (also called the Apostle Paul). If this is in fact the case, the writer of this gospel was the only non-Jewish author of any book of the New Testament. There is ample internal evidence that he was likely a proselyte to Judaism who came to believe Jesus was the Messiah. In addition, we could surmise that the work was influenced by the preaching and teaching of Paul, in addition to the accounts of eyewitnesses collected (Luke 1:2).

Many scholars believe that Luke was from Macedonia, perhaps a Philippian by birth. It is interesting to note that in the accounts of Paul’s journeys the author apparently joins Paul just before his dream of the Macedonian man that changed the course of Paul’s journey toward Macedonia (Acts 16:9ff). The dream corresponds with the author changing the pronouns of the journey from “they” to “we” suggesting that the author is now an eyewitness to that part of the journey. The same happens when Paul reached Troas on his third journey to the area (Acts 20:6). The final selection of “we” passages is the trip of Paul from Caesarea to Rome (Acts 27 and 28). It is likely these reflect that Luke was with Paul all the way to Rome and wrote the letter that became this “book” from that city.

A brief review of the Gospel According to Luke (Epic one)

The Gospel according to Luke appears as part of a series of personal letters to a man named Theophilus who was seeking information on the work of Jesus of Nazareth. The letter opens with a statement of the primary purpose of the account. By the time of the writing of this gospel, the writer claims that “many others had taken in hand to write the things which Jesus said and did” (cp. Luke 1:1-4) and this account therefore was a collection of eyewitness accounts that focused on the chronology of the life of Jesus.

The structure of the letter includes some unusual features. In addition to the special attention to medical matters (as one would expect from a medical doctor when authoring a work -4:38; 8:55), it also includes the most complete view of the events surrounding the birth and early life of Jesus. As a collection of reports, Luke has a keen interest in revealing a personal side of the ministry of Jesus, and takes specific care in personal accounts of Jesus with people like Zacchaeus of Jericho (Luke19), and a thankful healed leper in Galilee (Luke 17). His account is as full and careful as any other, but he offers special detail to the questionings and trials of Jesus, and to the scene of the Crucifixion. His Resurrection narratives include a long story of the personal encounter of some followers of Jesus that discover the Risen One as they travel the road to Emmaus. His citations of the Hebrew Bible lead some scholars to wonder if Theophilus (the recipient of the letter) may have been a Greek speaking Jew, or at least a proselyte familiar with some Jewish discussions and Scriptures. This occurs also in the Acts sequel, where Luke tells the time of the year by the Jewish feasts (Acts 27:9).

The Theme of the Book of Acts (Epic two)

The style of the writing of the Gospel according to Luke and the subsequent opening of the Book of Acts both suggest that this was a series of letters written to share the progress of the Gospel from its inception to the work of the early congregations and Messianic leaders. Perhaps along with the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts, there was a third document intended but never completed or lost in history (an unfinished trilogy?). Some speculate on a third letter, an idea fueled by the incomplete ending in the Book of Acts. Luke was an otherwise thorough author. The main characters and several issues are left unresolved, as though more were to follow.

The journey to Rome is given in an eyewitness account, and may indicate one underlying purpose of Luke’s letter. It may have been written to express to Theophilus “I guess you are wondering how a Physician from Philippi ended up in Rome attending a Jewish prisoner. Well it all started a long time ago when…”

Another theme is woven into the end of the account in Paul’s words from his final recorded sermon. In Rome the Jews refused to hear of God’s fulfillment of the Messianic promise in Jesus of Nazareth, so he took the message to the Gentiles. It seems important for Luke to point out to Theophilus that the Gospel was taken to the Jew first, but then presented to the Gentile as a result of continual resistance on the part of some in various synagogues. Paul consistently offered the Gospel “to the Jew first” as Paul reminds the Romans in his Epistle to them (Romans 1:16). When refused more opportunity by resistance, he turned “also to the Greek”. This seems to be highlighted in the accounts of Paul’s major works in each mission journey: at Pisidian Antioch (Acts 13:46) in the First Mission Journey; at Corinth (18:6) in the Second Mission Journey; and at Ephesus (19:9) in the Third Mission Journey. If part of the intent was not a treatise in defense of Paul’s methodology, Luke seems to be preoccupied with it.

The Story of the Book of Acts

This second letter written to Theophilus continues the story of the spread of the Gospel that he began in the Gospel According to St. Luke. This second epic opens with Jesus (after His death and resurrection) meeting His disciples and instructing them in Jerusalem. Jesus told them to gather and wait there until the coming of the Holy Spirit and then He ascended into Heaven. His disciples went back to Jerusalem and selected a replacement for Judas by casting lots. They narrowed the choices by character to two men: Joses (called Barnabas) and Matthias, who was eventually chosen. [Chapter 1]

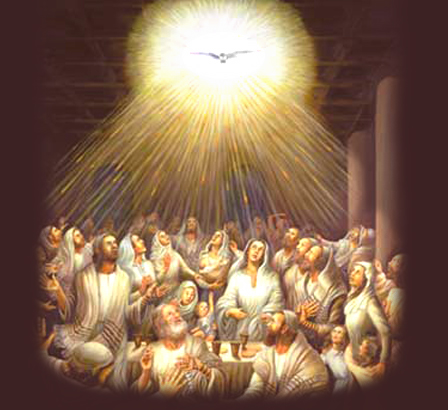

A short time later on the day of Pentecost, the disciples were together in Jerusalem praying and the Holy Spirit came upon them. This enabled them to tell the good news about the Lord in many languages that they had never learned before an international crowd of Jews gathered for the Feast. Peter followed the initial incident with an address to the excited and perplexed crowd explaining from the prophet Joel and from the words of David what had begun that day in their presence. He proclaimed salvation through faith in Messiah and more than three thousand people were saved. [Chapter 2]

These new “Messianics” were becoming known in Jerusalem, and began to care for one another. One afternoon at the gate of the Temple, Peter and John healed a crippled beggar who was asking for help. This caused quite a stir, as the people recognized him from the many times they passed by him and now saw that he could walk. They gathered around Peter and he explained that the power that healed the man was the power of the risen Messiah! He told the people they were guilty of killing Jesus, but that they could be forgiven of their sins by repenting and turning to the Lord. Peter and John were swiftly arrested and brought before the Jewish religious authorities who questioned them about the healing. They could find no wrongdoing by Peter and John and could not deny the healing of the crippled man, but they wished them to cease causing a stir among the people. They threatened the two and sent them on their way, recognizing the numbers of Messianic followers of Jesus were swelling to about five thousand! [Chapters 3-4]

The Messianic believers still worshipped in the courts of the Temple (mostly associated with Solomon’s Porch on the east side of the Temple plaza) and shared what they had with each other. Some sold property and then gave the proceeds to the apostles to distribute it as there was a need. These heartfelt acts of giving became marks of the followers of Jesus, and others began to mimic the giving, though not always for honest reasons, or with an honest heart. One such couple, Ananias and Sapphira sold a piece of land but kept some of the money back for themselves. When presenting the money to the disciples they evidently lied about the amount they were giving, making a show of the gift. Ananias died on the spot before the apostles. When his wife came shortly after, she also lied about the amount of money and fell over dead and was buried alongside her husband. News of the event made all of the believers carefully consider their hearts, and began a long journey of the need to constantly renew their walk with God. This internal situation was but the first challenge or test to the fledgling movement.

Because the group continued to gain in strength, the Temple leadership decided they needed to take action and imprison some of the Messianic leaders. While awaiting the hearing, an angel opened the cell and told the Messianic leaders to go back and preach in the Temple courts, so they left the cell and returned to the work. The High Priest was informed about the “escape” and had them brought into the council chamber for an immediate hearing. The Messianic leaders explained their message, and refused to refrain from preaching it. Fearing the response of the crowds and listening to some of the more moderate voices in the chamber, the Temple leadership allowed them to leave, and they continued to spread the message daily. [Chapter 5]

As the size of the work grew, the needs of those who joined to the message grew. The leadership was taxed, as it was not able to both seek the face of the risen Savior and care for all the followers in a way that met their needs. A third test faced the Messianics as some were complaining about the uneven meeting of needs. It appeared to the Diaspora (Greek speaking) followers of Jesus that they were getting neglected in comparison to the local Hebrew speaking followers. New leaders of character and faith were chosen, and the problem was handled by better organization.

During the time the Messianics were increasing in numbers, their message was being discussed all over Jerusalem, and the theological schools no doubt became heated with discussions of the merits of their claims. Some students decided to directly attack the Messianics, wholly disagreeing with the basic tenets of their message. Of the new group of seven Messianic servant leaders, one man named Stephen was singled out by a local Jewish Seminary for Diaspora students as a target of their wrath. After a lengthy defense which Stephen put before them and which they could not answer, they called on the Temple leadership to rescue them from the debate, and Stephen was brought before the council at the Temple. A long sermon followed, which illustrated the value of carefully examining the choice of these new servant leaders, and Stephen offered his defense of the Messianic message. He called on them to remember their history and the promises of God, and then told them Messiah had already come. Angry at his words, they took him beyond the wall of Jerusalem and stoned him there. One student held the coats, and stared as Stephen’s blood was spilt. He was Saul of Tarsus, who later became an important figure in the Messianic community. [Chapters 6-7]

Saul took on the attack of Messianics with great zeal, entering houses of suspected followers of Jesus and bringing them to prison. The followers began to separate and spread out, with some of the Diaspora Jews heading to their home countries with their new message. That was not the only way the good news that Messiah had come spread, however. God directed some like Philip, who was one of the servant leaders chosen by the people at the same time Stephen was chosen, to take the message to places in Samaria. After some remarkable movements of the Spirit of God there, Philip was compelled to go south along the road to Gaza. While moving along the road, he came upon a noble eunuch reading about the promise of Messiah, and Philip had the opportunity to share with him that Messiah’s promise had been fulfilled in Jerusalem. The eunuch had a desire to walk with the God of Abraham, but was not allowed to enter the Temple as a deformed man. After the man received his first opportunity of baptism, and knew God really accepted him, Philip sensed his mission there was complete, and left for Caesarea, preaching as he traveled. [Chapter 8]

Saul of Tarsus continued to cause real trouble for the Messianics; he had official letters allowing him to extend his search for Messianics to Damascus, trying to contain the spread of this growing Jewish movement. While on his way there, he was struck down on the road, and heard the voice of this same Jesus that the Messianics were talking about. He left the experience blind, with a promise that God was about to tell him what he should do for Him. Led by the hand, his companions brought him into Damascus, and Saul fasted three days waiting for instructions from God. Finally they came, and he was directed to Ananias, a man who had been given directions from God to lead Saul in his first steps of Messianic faith. Sight restored, Saul stayed for a time to share time with a small group of believers in Jesus. In a short time Saul began to preach the Messianic message in local synagogues, angering crowds that thought he was coming to shut down the Messianics. Some planned to kill Saul to stop the “defection” to the new message, and Saul escaped back to Jerusalem, being let down over the wall of Damascus in a basket. He was lead by Barnabas (the one who was not chosen to join the twelve in the cast lots at the beginning of the story), and taken to meet the Messianic Leadership. He remained a short time in Jerusalem, debating some from his old Seminary, and eventually returned home to Tarsus.

While Saul created a stir in the movement, yet another small group of followers faced intense pain over the loss of one of their key members. Shimon, called Peter, one of the disciples of Jesus who now helped lead the Messianic movement, was making his way southwest of Jerusalem, and had opportunity to heal some who were sick. The small group at Joppa heard of the healings and called on Peter to care for their loss, and return their dear one named Tabitha to life and health. Peter came and prayed for Tabitha, and her body was restored, causing the whole group to rejoice! Peter went to the house of another Shimon, who was a tanner, to remain with this small group for a time.

One afternoon, hungry and awaiting a meal, Peter was on the roof of Shimon’s house, and had a vision sent from God. The vision was of a sheet filled with animals that God had forbidden his people to eat. A voice told Peter to kill the animals and eat, but three times he refused, standing firm on God’s command. In the midst of the vision, a knock on the door of Shimon’s house brought Peter back to the moment. A centurion named Cornelius sent three of his soldiers to call for Peter to come to him in Caesarea. Peter, realizing that the vision of the animals was to call him to follow these three to the home of a Gentile, agreed to go with them on the following day to Cornelius. Peter offered the men lodging, and left the next morning. [Chapter 9]

After an eight-hour walk to Caesarea, Peter entered the house of the centurion and conversed with him, sharing with him and his household the good news of Messiah. God moved in the man’s heart, and the Spirit of God caused Cornelius to speak in a language he had not learned. With such an amazing demonstration of the power of God on his life, even the Jews were amazed that the good news was breaking into the heart of a proselyte who was not even circumcised! Seeing the work of the Spirit, Peter commanded Cornelius and his household to be baptized, and accepted them into the community of followers of Jesus. [Chapter 10]

News spread that Cornelius’ house had joined the ranks of the believers, and soon the Jerusalem leadership found themselves in a debate about this new ministry direction. Men of the leadership called on Peter to account how he could “eat” with a Gentile. Peter recounted in detail the whole move of God in his life. The room fell silent, as men of God saw for the first time the direction God was leading them toward. Peter finished, and the men agreed that God was opening the message to the Gentiles. They began to glorify God!

No sooner had the Jerusalem leadership acknowledged what God was beginning to do, than the Antioch believers began to see the door open in the hearts of Gentiles. Returning home when the persecutions, with arrests and Stephen’s execution were going on in Jerusalem, a small fellowship of Messianics was established in Antioch, preaching Messiah had come to the Jews. When they heard Gentiles were joining the movement, they opened the preaching of Messiah, and Gentiles responded. The Jerusalem Messianic leaders dispatched Barnabas to check out the growth. Thrilled with the work but seeing the need for depth in teaching, Barnabas went to Tarsus and brought back Saul to open a one-year series co-teaching the believers in Jesus at Antioch. During that year, a prophet had revealed that a famine was coming on the Roman world. The fellowships of Messianic followers and their new found Gentile believers took up a collection, and sent it to the Messianic leaders at Jerusalem to distribute it as they saw needs arise. The messengers entrusted to take the offering money to Jerusalem were Barnabas and Saul. [Chapter 11]

About the time the collection money was on its way, a government lead persecution of Messianics in Judea began under Herod Agrippa I. Herod decided the stir caused by the Messianic sect of Jews was an unhealthy influence on stability, and had James the son of Zebedee (brother of John), one of the Jesus’ disciples executed. When he saw his favor grow in the Temple leadership as a result of the execution, he decided to further it by taking Peter into custody. Because of the Passover, Herod held Peter in prison for execution after the feast. While there, Peter was held between two soldiers, chained in a cell as the fellowship at Jerusalem prayed fervently for his release. Late one night, the angel of the Lord freed him and told him to dress himself, opening each gate and leading him out of the civil prison, as he had years before from the Temple guard. Peter came to the door of the small fellowship that was deep in prayer for him. Startling the local believers, he came to the share the news of release. He told them to tell the other leaders, and then left to stay in Caesarea. A short time later, Herod Agrippa died in Caesarea and the immediate threat abated. To add to that good news, the offering money arrived in Jerusalem. After a brief visit, Barnabas and Saul returned to Antioch with Barnabas’ nephew, John Mark. [Chapter 12]

In Antioch, the worship time drew people into the presence of God. The Messianics began to be known as “Christians” (after the Greek term for Messiah). The Spirit instructed the believers to send out Barnabas and Saul to a work that He called them to. The congregation gathered together and sent them out with prayer and fasting. Departing Antioch with John Mark attending their needs, they walked to the port of Seleucia and caught a ship to Cyprus. Landing in Salamis, they preached the Messianic message in the synagogues and then traveled to Paphos on foot. While at Paphos, Saul and Barnabas were sent for by Sergius Paulus, the Proconsul. As they shared with the Proconsul their message, a certain sorcerer tried to keep him from believing. Saul (usually called “Paul” in Gentile areas) called on God to blind the sorcerer and he was blinded. Seeing this power, Sergius Paulus believed the message of Jesus.

Setting sail from Paphos, the three messengers of Messiah made their way north to Perga in Pamphylia. When they arrived in Perga, Paul was dominating the party. John Mark decided to depart the team and return to Jerusalem, apparently not liking the change in leadership. Paul (Saul) and Barnabas made their way through the Taurus mountain pass, and came into Antioch in Pisidia. That Sabbath, Paul preached a stirring message to the congregation about the coming of Messiah. Some Jews and some proselytes came to faith, while Gentiles requested that next week they be allowed to hear about Jesus. The following Sabbath Paul again preached to a vast group in the city, many of them Gentiles. Jews that had not believed the message of Jesus began to heckle them, but Barnabas and Paul spoke zealously that the message was to be for Gentiles as well, and many believed. The synagogue leaders who were against this preaching went to the city council and had the Messianics expelled. Paul and Barnabas moved on the nearby Iconium, but the believers in Pisidian Antioch remained and rejoiced in their newfound faith. [Chapter 13]

In Iconium, the Messianic messengers preached and debated, as many believed, both Jews and proselytes. After preaching and some amazing demonstrations of the power of God, the city was divided between those who believed and those who thought the message a hoax. Those who did not believe the message wanted to catch the men and stone them. Aware of the rising tide of trouble, Barnabas and Paul fled to the nearby Roman colony of Lystra in Lycaonia, a pagan city with no synagogue. Believing that God had opened the door for Gentiles to receive Messiah, they preached the good news that a relationship with the God of Abraham was possible for them. After healing a local boy who was born lame, people in the town began to worship them as manifestations of the pagan deities. As they assembled to offer sacrifices, Barnabas and Paul tore their clothes and begged the people to see them as mere men. After some time, some instigators of trouble came from Iconium and Pisidian Antioch and convinced the people of Lystra to have Paul stoned and left for dead. After the stoning, the believers gather outside the city around the body of Paul, and Paul got up and went home with them. The next day the men left Lystra and journeyed to Derbe, preaching to the people there. After a good response, they returned the way they came, checking on each small congregation as they returned through Lystra, Iconium and Pisidian Antioch. They returned to the coast of Pamphylia, preaching again in Perga, and returning to a ship at Attalia. They sailed back to Antioch filled with awe at what God had accomplished, and shared it for a season with the Antioch followers of Jesus. [Chapter 14]

In Antioch there were Messianic followers of Jesus from Judea who insisted, “One who is not circumcised according to the Torah of Moses cannot be justified before God.” When Paul and Barnabas came to Antioch, they disagreed and a debate ensued. The question was submitted to Jerusalem’s Messianic leadership, and a council of key figures of the movement was convened at Jerusalem. The debate was long and difficult. Peter argued that God had also chosen Gentiles and demonstrated that fact a long time ago. He saw no difference in the essential faith that lead to their justification, though in practice they remained different. He did not want the yoke of “living as a Jew” to be placed on their lives, with all its weight. Paul and Barnabas testified next, arguing that the work of the Spirit was clear in the lives of the Gentiles.

An Apostle named James (the half brother of Jesus and writer of the Epistle of James) presided over the meeting, and brought the concluding judgment in the matter. He stated that God was at work in the Gentiles, and they had no place disregarding this fact. He disregarded the suggestion that Gentiles needed to physically identify with Israel’s covenant symbol of circumcision and become part of Israel physically. He also distinguished the need for Gentiles to follow four specific commands that clearly separated them from their pagan past. He commanded that they: 1) abstain from idol offerings at pagan temples; 2) abstain from any pagan blood rituals; 3) abstain from idolatrous sacrifices even if they are bloodless and include only strangulation; 4) abstain from the sexual sin so much a part of their temple practices. In general, James said they must leave the paganism that pervaded their lives before, to clearly follow after Jesus. If they avoided these things and trusted in the atonement of Messiah alone for justification, they did not need to become a physical part of the Abrahamic covenant of promise to the sons of Isaac through Jacob, nor subject themselves to all the Torah standards associated with Israel’s inheritance.

In addition to the pronouncement to the Gentiles, James made no change in the ruling concerning Torah commands to Jews, simply adding that Moses was explained to all of them in their home synagogues every Sabbath. With that the council wrote the judgment in letters, and sent it out to the various congregations, restating the words of James. Letters were given to Paul and Barnabas to carry abroad to the congregations, while verbal testimony of Judas and Silas would reinforce the veracity of the report of the ruling. The letter was issued, and the teams were sent out to settle the matter in the congregations, beginning with Antioch.

Judas and Silas taught the ruling of the council to the congregation at Antioch, and Paul and Barnabas brought the letter. A short time passed and Paul asked Barnabas to accompany him on another outreach journey. The two could not agree on whether to offer another opportunity of participation to John Mark. Paul decided to go with Silas to the works in Pamphylia and Pisidia (the mainland areas of the previous journey), and Barnabas took John Mark to check on the Cypriot congregations (the island area of the previous journey). [Chapter 15]

Paul and Silas made their way through Syria past the famous battle site of Issus, and through the “Cilician gates” into Pisidia, where they visited the believers at Derbe and Lystra. At Lystra they added to their team a young man named Timothy of mixed birth (father Greek, mother Jewish), and Paul circumcised him. Paul knew the Jews of Pisidia would watch carefully how he treated the Torah in the life of a non-observant Jew. They saw the churches were growing and strong, and moved north and west through the lake district that lead to Phyrgia, and into southern Galatia trying to move west to Asia Minor. The Spirit led them north to Mysia and the city of Troas near the Hellespont. When the team arrived in Troas, they met Luke the Physician, who had come from Macedonia (possibly from his home in Philippi). Paul was wrestling with the direction, and his desire to go into Asia Minor to great cities like Ephesus, Pergamon, Miletus and Smyrna. As he slept in Troas, a vision of a man from Macedonia (probably the physician Luke) called to him and requested help. Paul knew it was God’s call to move west into Macedonia, so he immediately looked for a ship to take him across the northern Aegean Sea.

The four men took the boat from the harbor near Troas, and went overnight by ship to harbor in at Samothrace Island. The next day they moved on to Neapolis, where the team disembarked and traveled on foot over the mountain ridge to the Roman garrison and colony at Philippi. Finding no synagogue that Sabbath, the team made their way to the nearby stream to pray and worship (a common Jewish practice in such circumstances). At the stream a Thyatiran woman named Lydia heard Paul speaking, and was drawn to the message of Messiah. Yielding her heart, she was baptized. Afterward, she asked the team to come to her home and stay there.

As they continued in the city, they had regular times of prayer and met together. During one such occasion a young demon possessed slave girl kept harassing Paul and the others, and Paul commanded the demon to come out. With the exorcism, the owners of the slave girl lost the revenue her “gifts” provided, and complained to the magistrates of the city, falsely accusing Paul and Silas of subverting some Roman laws. The crowd seized the two, pulled off their clothes, beat them with lashes, and then imprisoned them without proper trial. Night fell, and Paul and Silas sat in their cell singing and praising God, when an earthquake opened the gates. The jailer saw the openings and thought he would be executed in humiliation when the prisoners under his charge escaped, but Paul cried out to him, “Do yourself no harm, we are all still here!” The jailer’s heart melted and Paul and Silas shared the good news of Messiah with him. He accepted the message of Jesus, and took the men out of their cells to his home. He washed their wounds, and returned to the jail with them. In the morning the magistrates sent a message to let them go, but Paul refused to leave without an apology. Paul was a Roman citizen and was imprisoned and beaten without proper trial. When the magistrates heard he was Roman they came to him and asked him to leave town. Paul and Silas left the prison, visited Lydia and the other followers of Jesus, and then depart westward along the Via Egnatia. [Chapter 16]

Passing through the cities Amphipolis and Apollonia – Paul, Silas and Timothy headed directly to Thessalonica, where there was a Jewish community and a synagogue. Their host in the city was a man named Jason (and was likely a relative of Paul). The team arrived and Paul debated for three Sabbaths in the synagogue, explaining in detail that Messiah was promised and had come, suffering for them. A number of proselyte Greeks believed, as well as some prominent women in the synagogue. Among those who did not believe were some influential Jews who pressed a mob into pulling Jason from his house and placing him under bond. Paul agreed before the city council to leave and Jason was released. Paul and Silas said goodbye to the believers and slipped away in the night to Berea.

At Berea the team found an anxious audience that listened intently and tested everything that the Messianic teachers told them. Men and women both studied with them, and many believed, including some prominent proselyte men and women. Soon some of the Jews of Thessalonica who did not agree with the Messianic message found out about Paul and Silas’ work in Berea, and came to disrupt the teaching. Those who believed gathered and determined it was best if Paul leave. Silas and Timothy remained in Macedonia, and Paul left to Athens alone by ship.

Paul’s stay in Athens was a time of challenge. He was without the team, had experienced the pain of persecution, endured physical beating, and had an intense desire to go back to Thessalonica. Wrestling with these issues, he encountered the world center of pagan philosophy at Athens and was deeply stirred. He directed his first speaking in the synagogue but made no real progress. He turned his attention to the marketplace, encountering a number of philosophers and temple attendants. His preaching drew enough of a crowd that he was whisked off to the guardians of the teachings of the market, “the Areopagites.” Paul offered a sermon that included quotes from two famous Greek poets and was mocked by some of the hearers. By the end of his time in Athens, he saw God draw a few to the faith, including Dionysos the Areopagite and a woman named Damaris, with a handful of others. Paul left alone on foot by way of the ceremonial Roman road that passed the Eleusian temple of Demeter and Persephony, and made his way to Corinth. [Chapter 17]

By the time Paul got to Corinth, discouragement set in and he needed a lift from God. The encouragement began in the form of some new Jewish friends named Aquila and Priscilla who shared the same craft of tentmaking. Though he spoke each week in the synagogue, his real boldness to share the Messianic message returned when Silas and Timothy came and refreshed him with news from Macedonia. With poor reception from the officials in the synagogue (with the exception of the chief ruler named Crispus) Paul decided to turn his attention to reaching Gentiles in the city with his message. Many Corinthians believed and were baptized. Still Paul held back. He had suffered deep wounds on the journey, and needed a profound meeting with God. A vision came in the darkness of the night. Jesus came to Paul and assured him that if he would remain in the city, he would be protected from further attack. Paul believed, and remained there another eighteen months. It was apparent his promise to remain there became a vow before the Lord, not completed until the eighteen months was passed.

Even when tested before Gallio the consul of Achaia, Paul knew that God would protect him. The new ruler of the synagogue (named Sosthenes) who replaced the now Messianic Crispus brought Paul to the judgment seat, but Gallio threw the case out. Then Sosthenes was taken and beaten by some locals with the court refusing to intervene. The disinterest of Gallio in perceived internal Jewish issues allowed the work to continue until the consul’s term was over. Paul left about that time to the nearby eastern port of Cenchrea.

Looking out over the Saronic Gulf, Paul could see in his mind’s eye all the way back to Jerusalem. It had been a long time since he was comfortably in the halls of the kosher friends at Jerusalem, and he missed them. He shaved his head, having completed his vow to serve Jesus in Corinth and gathered his friends for a farewell. He took a boat east with Aquila and Priscilla to Ephesus and spent a short time in the synagogue teaching. He left his friends there, and continued on to Caesarea, to the feast in Jerusalem, and eventually back to Antioch.

After some time, Paul decided to travel to the established congregations in Galatia and Phrygia. At the same time, other followers of Jesus were spreading the message to the Roman world. One such man was Apollos of Alexandria who was teaching and evangelizing effectively in Ephesus. He met Aquila and Priscilla there, and they added some details on baptism to his message that greatly aided him. After some challenging ministry in Ephesus, Apollos went on to Achaia and took up teaching believers in Jesus in Corinth. [Chapter 18]

While Paul was passing through Mysia venturing south to Ephesus he came upon a group of a dozen believers that had been taught by Apollos before he was instructed in the work of the Spirit by Priscilla and Aquila. Paul told them of this work and they experienced powerful manifestations of it, prophesying and speaking in unlearned languages. Paul remained there, teaching in the synagogue for about three months, until he realized that no one else there would believe in Jesus. Then took the believers next door to a local school, continuing to teach for two more years. God used Paul mightily, showing miraculous works through him, healings and the casting out of demons. Many idolaters turned to faith, and those in the black arts destroyed their evil books of incantations and spells.

After these years, Paul knew it was time to move on and check on the believers in Macedonia and Achaia. Paul saw things turning for the worse in Ephesus and delayed his departure for a bit. He sent Timothy and Erastus to check on the Macedonian believers. While they were gone, the Messianic believers got into trouble with the local guild of metal workers, who made their income by creating small replicas of pagan gods. Demetrius, the silversmith, lead the riot to get rid of Paul, whose ministry was killing their market. Gaius and Aristarchius both of Macedonia were fellow workers of Paul. These two were caught and taken into the theatre. The town clerk saw the mob and tried to listen to their grievances, but finally dismissed the assembly as illegal. [Chapter 19]

Hostilities quieted and Paul felt he could leave. He journeyed to Mysia and came to Troas on foot. There he met a delegation of several friends that went before him into Macedonia and returned. This select group of friends included Sopater of Berea, Aristarchus and Secundus of Thessalonica, Luke the physician (probably of Philippi), Timothy of Lystra, and Tychicus and Trophimus of Ephesus. The whole group came to Troas after Passover, waiting there for Paul to join them. When Paul arrived they celebrated and shared in a meal together, followed by an extended study that lasted until dawn! During the meeting a young man named Eutychus fell asleep listening and tumbled from his spot on a window ledge to the floor. People gathered around and presumed him dead, but Paul came over him and raised him up. The people were relieved, but Paul got up and continued with the lesson! Paul sent the team by ship from Troas to Assos, but decided to walk alone and met them in there.

From Assos, Paul joined the team and sailed to Mytilene on Lesbos Island, harboring overnight. The next day they continued to Chios Island, another day to Samos Island (with an overnight at Trogyllium), and finally landed at Miletus. Paul had only been gone a short time out of Ephesus, but he felt that he may not get the chance to return to them in Asia Minor so he gathered the elders of the congregations together (including those of Ephesus). At Miletus, Paul delivered one of his most difficult emotional sermons. He told them they would not see him again, and they wept. After a time of prayer together, they took him to the ship and waived goodbye to this one who had shared the good news so tirelessly among them. [Chapter 20]

The ship journey took the team for brief stops at Cos, Rhodes and Patara. In Patara the team found a ship that was set to sail for the Phoenician coast. The ship sailed south of Cyprus directly to Tyre and offloaded her cargo. The team sought out local believers and met with them for seven days. During that time, several Messianic followers declared that the Spirit was warning Paul not to go up to Jerusalem. After the week of sharing, the believers prayed together and the team boarded a ship to head south. Following the coastline, they harbored the next day in Ptolemais, with time to visit the local believers there for one day. From Ptolemais, the team came into the great harbor at Caesarea.

At the modern and bustling port the team found their way to the house of Philip, one of the seven servant leaders chosen in Jerusalem years ago. Paul was in no hurry; he was refreshed to be back on Judean soil with a great company of friends from all over his ministry! While he was there, God sent a messenger to him, a prophet named Agabus (who had predicted the Roman world’s famine years before). When the prophet came, he tied up Paul, and told the team that Paul was about to face such an arrest by Jews who did not agree that Messiah had come, and an imprisonment at the hands of the Gentiles. Though greatly urged to stay away from Jerusalem, Paul would not back off his plan and told them he was ready for what God had told them.

Hiring horses for the trip, Paul and the team made their way up to Jerusalem. Joining the ever-swelling ranks of the team were some Messianic followers from the Caesarea congregation, as well as Mnason of Cyprus, who had a house in Jerusalem. When they arrived in Jerusalem, the Messianic leaders warmly embraced the team, and assembled a meeting with James and all the leadership. They listened intently as Paul shared what God had done in the ministry to the Gentiles. They were excited to hear his account, but were also burdened by outside reports that had come back to them of his ministry.

Some had reported that Paul was telling Jews that lived in the Diaspora not to keep the Torah, but rather to forsake the ways of the inheritance that the Fathers had instructed them. The leadership reiterated the council finding of the Jerusalem Council, and made sure the team understood that their ruling was only for the Gentiles, and should not have affected the way the Jewish believers in Jesus behaved. They wanted to be clear, Gentiles needed to leave idolatry and cling to Jesus, but Jews needed to remain as Jews, clinging to justification through the blood of Messiah alone. To make the message clear that Paul was still walking according to the Torah, they instructed Paul to take four Jewish men who had taken a vow to the Temple to offer sacrifices. Paul did as he was instructed, was ritually bathed and got himself ready for seven days to bring the sacrifice necessary to complete the vow.

The day came to take the men, and Paul went into the Temple with the men as well as some of the Messianic team from Asia Minor. Some people in the Temple saw him and stirred up the people, accusing Paul of bringing in Gentiles to the inner court of the Temple, because they had seen him earlier in town with Trophimus, his team member from Ephesus. Paul was taken away and the inner court Temple doors were closed. The crowd gathered to kill him, pulling him toward the outer gate and beating him. Meanwhile news came to the Roman guards of the adjacent Antonia Fortress that a riot had broken out. Roman soldiers were dispatched and took Paul from the hands of the angry crowd.

As he entered the fortress, Paul turned to the captain of the guard and spoke Greek to him. Startled, the captain asked his identity, and Paul identified himself as a Jew of Tarsus. He asked if he could address the people under the protection of the Roman guard on the stairway, and the captain agreed. Paul turned and spoke in Hebrew to the crowd. He delivered a powerful testimony to what God had done first in his life, then in the Messianic movement. When he reached the part of the message where God had sent him to Gentiles, the crowd roared and shook the dust of their sandals into the air. The captain ordered Paul brought inside. Binding him for a lashing, Paul told the soldiers he was a Roman citizen, and they warned their captain to be careful how they handled him. The captain came to him and asked him directly if he was a free citizen. When Paul made it clear that he was, the captain loosed him and kept him inside the Antonia. [Chapters 21-22]

The next day the Claudias Lysias (the captain of the guard) sent word that he wanted a meeting with the council and with Paul to settle the matter. Paul came before the council and proclaimed he was innocent of all charges. The High Priest commanded those who held him to strike him on the mouth. Paul chided the High Priest (not knowing it was the High Priest) and complained that he was struck unlawfully. When the chamber called on Paul to reckon why he upbraided the High Priest, Paul apologized and told them he did not know whom it was that he was addressing (recognizing it was unlawful to chide the High Priest). When Paul saw the room was composed of both Pharisees (who believed in afterlife) and Sadducees (who did not), he proclaimed that he was a second generation Pharisee and was brought in because of his defense of resurrection and afterlife. The debate that ensued became a pulling match, and Claudius Lysias had Paul taken away, fearing he would be ripped apart in the scuffle. Paul was taken back to the Antonia.

Late the following night Paul awoke to find Jesus standing beside him. Jesus spoke words of encouragement to Paul just like he had at Corinth so long ago. He told Paul that he would be called on to go all the way to Rome with the message he preached in Jerusalem. With that Paul rested and knew that his death was not imminent.

The next morning a small band of men prepared to kill Paul. They vowed to fast until he was dead, and told the Sanhedrin council to call for him to be re-examined. Their plan was to kill him on the way to the meeting, but Paul was warned by his nephew and relayed the plot to Lysias. The captain sent a large contingent of soldiers with Paul under protective custody (accompanied by a letter that explained his actions) to the seat of the Roman Procurator named Felix at the port city of Caesarea. In his letter he explained that he saw no reason to hold Paul, but felt the need to protect him as a Roman citizen. Paul was taken away by way of Antipatris and eventually to Caesarea for an audience with Felix. Felix ordered him held and said he would hear the matter when his accusers were assembled. [Chapter 23]

Five days later, the High Priest Ananias and a delegation came from Jerusalem, together with their lawyer Tertullus. The lawyer indicated (after am extremely complimentary opening) that Paul was a seditious fellow, spreading insurrection among Jews and desiring to defile the Temple. He argued that Paul would have been killed under Jewish law had they not been disrupted by Roman guards. Paul got an opportunity to answer the charges. His points were clear and simple. He said he had only been in Jerusalem twelve days ago, and there was no evidence of him having any dispute, raising any issue in the Temple or in any local synagogue. He argued they lacked evidence because their charges were false. He then restated for the record that he considered himself Jewish and kept the law as was common to Jews in Jerusalem, but was being persecuted because he believed in the resurrection of the dead. Felix decided to wait on the arrival of Claudius Lucias to see if his testimony would clarify the accounts. In the end, Felix called for Paul to explain his message on several occasions, even before his wife who was a Jewess. In the end, he left the issue for his successor, and Paul awaited judgment for two years! [Chapter 24]

After the new Procurator, Porcius Festus, came into the office, he made a trip to Jerusalem. The High Priest and a delegation met with him and requested that Paul be sent back up to Jerusalem and put back in the jurisdiction of the Temple court. Festus decline, but did offer them the opportunity to present their case anew before the judgment seat in Caesarea. Paul came before Festus and boldly charged that there was no evidence he had done anything improper under Jewish or Roman law. Festus offered to have him sent to Jerusalem and put under Temple jurisdiction and Paul appealed to Caesar (Emperor Nero) to be held under Roman law. Festus closed the case of jurisdiction by declaring that Paul had the right under Roman law to appeal to Caesar, and he had to be sent to Rome for a hearing. [Chapter 25]

During the time Paul awaited his trip to Rome, he was called on by Procurator Festus to tell his story to Herod Agrippa II and his consort Bernice. Agrippa was a Jewish client king who served under Romans. Genuinely interested, Agrippa called on Paul to give an account of himself. Paul carefully explained all that had happened to him, from the vision on the Damascus road and the message of the risen Messiah. Agrippa told Paul, “You almost have me to persuaded to join the Messianics!” Agrippa admitted afterward to Festus and Bernice that Paul was guilty of nothing. He expressed, “Had Paul not made the appeal to Caesar (a matter of Roman jurisdiction) he may have been set free.” [Chapter 26]

Luke and Aristarchus of Thessalonica joined Paul for the journey to Rome. The prisoner ship was under the penal supervision of an Imperial centurion named Julius. They launched out to the north, and briefly stopped in the port of Sidon, where Julius allowed Paul to refresh himself in a local friend’s home. Launching from there, they sailed south of Cyprus because north winds were making travel difficult. They turned north to Myra, along the coast of Lycia.

In Myra, Julius found a large ship of Alexandria that was heading to Rome and put the prisoners on it (the ship had a total complement of 276 people). The ship left port, but had barely any wind and traveled painfully slowly along the southern coast of Asia Minor, finally crossing into the Aegean Sea to Crete, where they harbored in the southern area called the Fair Havens, near Lasea. Paul warned them it was too late in the year to attempt the journey to Rome, but the captain of the boat felt he could make it, and did not like the conditions wintering in Fair Havens. Loosing from port, the ship was caught in a strong northwesterly wind that drove the ship beyond the ability to direct the sails, so they did their best to steer west, crossing below the island of Clauda. The timbers were loosening as a result of the fierce wind strain, and the sailors tried to keep the ship together. Caught in open sea and pulled by fierce winds, they lightened the ship on the second day, but the storm did not still. Days passed and the ship was pushing toward Sicily, but the situation grew desperate.

After a long time in the terrible storm, Paul had a message sent from God by an angelic vision. He told the crew that no one would die but they would lose the ship and be grounded on a small island. Fourteen days into the storm they knew they were coming close to landfall. Sounding depths, they got as close as they dared in darkness, dropped anchor, and waited for sunrise. Some shipmen began to lower the launches, but Paul warned the Julius and his men, “Unless these men stay on the ship, you will not be saved!” Julius had his soldiers cut the ropes, and the boats dropped into the sea.

Paul urged the whole complement, in the midst of the storm to stop and eat something. He reiterated to them that no one would die, blessed God for the bread and began to eat. The crew and prisoners ate, and then cast the rest of the cargo overboard to lighten the ship. After daybreak, they took up anchors, loosed the rudder and hoisted sail. They ran the ship aground and she began to come apart. The soldiers turned to execute all the prisoners, but Julius (in order to save Paul) told all prisoners and crew to swim for shore. As the ship broke up, the whole complement swam ashore or held to pieces of the ship to arrive to shore, but no one was lost. [Chapter 27]

Soaked but safe on dry land, the ship re-gathered its crew and prisoners on the island of Melita (Malta). The local people did not speak Greek, but they did show kind hospitality. While Paul helped to gather firewood, he was bit by a poisonous snake, but shook the snake into the fire. At first people thought he must have been a terrible criminal who was getting his justice, but when he did not swell or die, they thought him a god!

A local man named Publius offered lodging to Paul and his companions. Publius’ father was dying of dysentery, and Paul healed him. As a result, after the three days the team stayed there, people kept bringing their sick to Paul for healing. People openly expressed their thanks, and gave Paul and the whole company things they needed for the journey. Their time on the island lasted three months as they awaited another transport vessel to Rome. They were put aboard a ship of Alexandria, bearing the sign of “Castor add Pollux” and sailed for Syracuse on Sicily. After a brief three-day stop, they landed at Rhegium in southern Italy. Another brief stop and they continued on the journey north to Puteoli, catching good winds and making the trip in excellent time. At Puteoli the team met some of the faith, and remained with them for a week. News of their arrival reached the area congregations, and when they began to journey toward Rome they met believers in The Appian Forum, and even more in the Three Taverns area. Paul’s heart was filled with thanks as he saw what God had done to spread the message of the Gospel. When they reached Rome, all the prisoners were surrendered to the common prison, but Julius assigned a protective guard to Paul and arranged private lodging for him.

A few days after they arrived, Paul called for the Jewish leadership of the area to meet with him to explain why he had been sent there from Jerusalem. The local leadership had received no word from the Temple leadership and was totally unaware of Paul’s case. Paul had the chance to explain to them the story of the good news, and he wasted no time doing so. After his message, the leaders left discussing it among themselves. Paul hired a house and remained under guard for two years in Rome. During that time, he preached and taught openly, and no one tried to stop him. [Chapter 28]

The Emphasis of the Book of Acts

The Book of Acts is a complex letter. It appears that part of the letter was written to catalogue the spread of the Gospel geographically to various people groups. Luke probably intended to offer evidence of the fulfillment Jesus’ promise before His Ascension from the Mount of Olives: “You shall be witnesses to me in Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria and to the uttermost parts of the earth” (Acts 1:8b). The letter seems formed around this geography, with the movement of the Gospel in Jerusalem (Acts 1:1-8:3), Judea and Samaria (8:4-40) and beyond (9-28).

Within the geographical frame above, Luke also clarifies some of the key challenges faced by the early Messianic movement. He appears to systematically move between the internal and external crises of the believers. In the early stage of the narrative he mentions the frequent threats against the Messianic leaders by the Temple authorities (4:3-7; 5:17-27), which led to the stoning of one of the Messianic leaders (6:8-7:60). Later external pressures included the rampages of Saul of Tarsus that ransacked the houses of suspected believers in Jesus in a manhunt (9:1-5). In addition to the external pressures, the movement internally fought against complaints of inequity in matters of finance among its members (6:1-7), and even lying in matters of property between followers (5:1-11). The leadership struggled to define the community of believers, and attempted to reconcile the promises of the Hebrew Scriptures to the reality of the work of the Spirit in the Gentile born followers of Jesus (Acts 11:1-18; 15:1, 6-35; 21:21-25). This pressure plagued the Messianic movement throughout the period of the writings of the various letters of the Apostles to the congregations (Epistles).

Another emphasis of the letter includes an insightful narrative of the chief personalities of the leaders in the new movement. Biographical sketches are drawn from the glimpses in the letter of individuals like Peter (2:14-5:42; 9:32-11:18), Stephen (6:1-7:60), Philip (8:1-40), Barnabas (11:19-30; 13:1-14:28) and of course Paul (9:1-31,11:25-30, 12:24-14:28, 15:36-28:31). This view of the leaders is critical to our understanding, since it is often difficult to see a balanced perspective of the leaders from their writings. Many Epistles address certain arguments or problems in the fledgling congregations, without giving a sufficient background of the writer. This narrative gives a cross reference to a number of their struggles, and offers context to their other writings.

One of the most critical features of the letter is the explanation of the so-called “New Covenant” and its beginnings in the Gentile world. The Hebrew Scriptures promised that a “New Covenant” was coming to the Jewish people. A careful study of the Hebrew texts of this covenant offer no hint that Gentiles would in any way be a part of the plan. In fact, the covenant as it is described in the Hebrew Scriptures is primarily about the return of the people to the land and their hearts to the God of Abraham (Jer. 31:27-40; 32:37-40; Isa. 59:20-21; Ezek. 16:60-63, 37:21-28). One of the specific purposes of the letter to Theophilus appears to explain that while this is completely true, it was not complete. The New Covenant, according to Luke, BEGAN with a small number of Jews (cp. Acts 1 and 2), then entailed a dramatic conversion of many Gentiles (Acts 10:28-29) and would eventually END with the fulfillment of a Kingdom of Jews that knew their Messiah (Acts 2:17-21). The expansion of the New Covenant to include the Gentile was probably the dominant theme in the latter half of the letter.

Finally, there is ample evidence the letter intended to offer a new and expanded explanation of the nature of the God of Abraham. Since the world of the Jews was thoroughly monotheistic, the letter attempted to offer some small explanation to the Messianic view of God. This view was an expansion of the traditional Jewish approach, not an attempt to depart from it. The view of the Hebrew text was simply that God is One. The view of the Messianic believers was that the one and only true God revealed Himself in a variety of personality roles. Each personality role was complete: independent in intellect, emotion and will. In that way, the one God was multiple in personality, but, in contrast to paganism, God was not multiple in Essence – thus an extension of the essential Hebrew monotheism. The difference may appear slight, but to the Apostles it was the marking line between a pagan view, and the view consistent with the Hebrew Scriptures, which they viewed to be the exclusively true Word of God. Examples of this in the letter appear in the personification of the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:2,5,8), the Heavenly Father (1:4) and the obedient Son (2:27). Special emphasis in the sermons of the Apostles show a distinction of personality between each of the three (Acts 2:32-33). In that way the Messianic movement believed that their approach offered an expanded view of the God of Abraham.